It was March 2020 and Jim Montecucco was desperate to ski.

Seattle-area resorts had closed due to the COVID-19 pandemic, so the 58-year-old Kirkland resident hauled out a backcountry ski setup he had purchased in 2018 but never used. He called up fellow Kirkland resident Richie Tagliano, a snowboarder, and the duo headed to Snoqualmie Pass determined to make their way up a slope and slide down it — even if they weren’t entirely sure how to go about skiing with no chairlift.

“I didn’t even click into the gear until they closed Alpental,” Montecucco said. “I tried it on in my living room and didn’t try it on again until I was in Great Scott.”

That the two lifelong skiers even made it to Great Scott Bowl, an alpine zone at the head of the Alpental Valley, was itself a feat. Tagliano wore soft snowboard boots and Montecucco hiked alongside him in ski boots, the two postholing their way 3 miles up the Source Lake Trail. At the bottom of Great Scott Bowl, they set their sights on Pineapple Pass, a well-known backcountry ski destination just beyond the Alpental ski area.

After the arduous hike in ski boots, Montecucco switched over to his untested backcountry equipment — namely, skis with alpine touring bindings that can rotate between a locked heel to ski downhill and a free heel to go up with the help of climbing skins, which have glue on one side to stick to the skis and fabric on the other to create friction with the snow. He attached the climbing skins to the tip and tail of his skis, but didn’t remove the skin saver, a protective mesh sheet that sticks to the glued side, effectively creating a banana peel effect between his ski and the snow.

He promptly fell over.

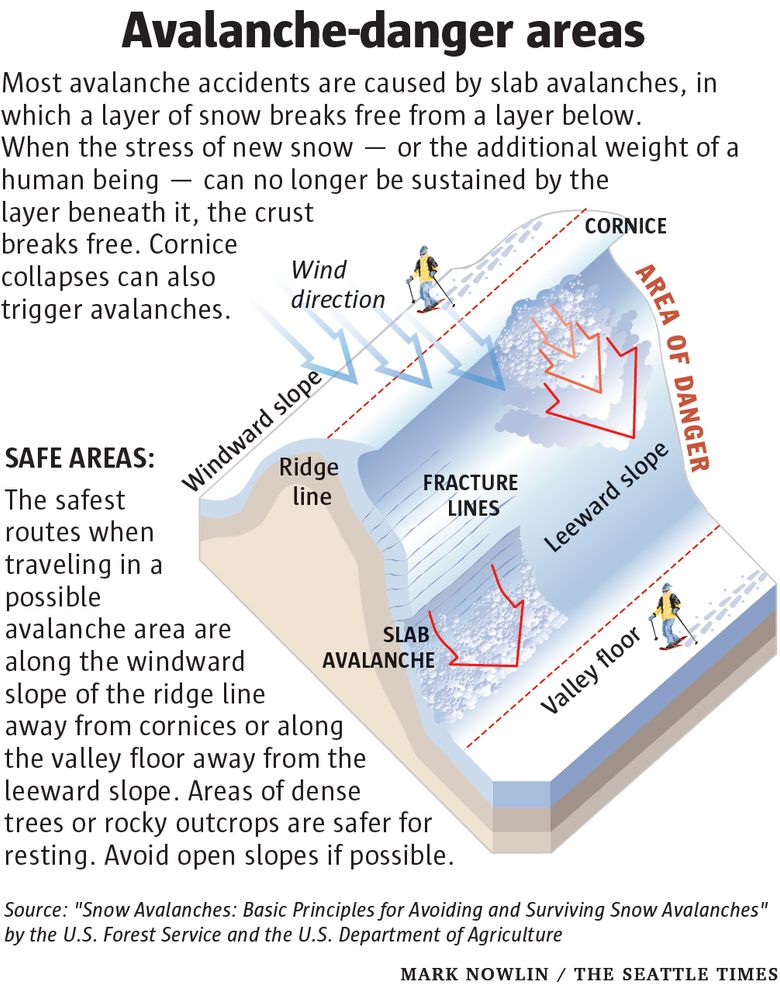

Once Montecucco figured out he had to remove the skin savers, he fared better. But Tagliano forgot his poles, so Montecucco lent his set. Tagliano hoofed it through deep snow, his snowboard strapped to his back, while Montecucco struggled to ski uphill without poles for balance. At switchbacks in the skin track, an ascending route impressed into the snow by prior backcountry skiers that day, Montecucco flopped onto his back like a turtle and threw his skis across his body before struggling to push himself upright. To cap off the misadventure, they had only one set of avalanche safety equipment — a shovel, beacon and probe — between them.

“That was a disaster,” Montecucco recalled nine months after his initial backcountry outing. Still, the friends kept at it throughout the spring with plenty of trial and error, including gear upgrades (Tagliano bought a splitboard, a snowboard that separates into two skilike parts to allow uphill travel like backcountry skis), and Montecucco purchasing an avalanche air bag pack on his wife’s insistence.

“We made a lot of poor judgments. As we started getting better, we realized we were doing so much wrong that we had to pump the brakes and make it a more serious endeavor,” Montecucco said.

The COVID-19 pandemic has accelerated a lot of incipient trends, from e-commerce to telehealth. Add backcountry skiing to the list. The premature end to the 2019-20 lift-accessible season is still a fresh wound to many skiers, leaving the prospect of a full winter of ski resort operations an unknown variable. Even if resorts do stay open, new requirements like daily reservations, limited capacity on chairlifts and a lack of indoor amenities turn some off. For many Seattle-area snow lovers, equipping for the backcountry is arguably a more reliable way to guarantee a ski season, even if that means spending the vast majority of the day skiing uphill to log a handful of downhill runs.

Snowsports Industries America, the winter sports industry’s trade group, estimates there were 1.357 million backcountry skiers and riders during the 2019-20 season in what has become the fastest-growing segment of the ski industry. If sales figures from local ski shops are any indication, those numbers are expected to balloon in the Cascades this winter.

Ascent Outdoors in Ballard has beefed up its rental fleet and reports over double the sales figures of alpine touring gear this fall as compared to last year, with specific shortages in alpine touring boots. At Seattle-based evo, climbing skins, splitboards and splitboard bindings are hard to come by. This season, the company’s Seattle flagship store has added “backcountry setup” as a dedicated appointment slot alongside its usual boot fittings. Three photographic guidebooks to backcountry skiing in the Cascades by Seattle-based guide Matt Schonwald sold out and had to be reprinted by their publisher.

But the sudden enthusiasm for uphill skiing also creates the prospect of more dangerous backcountry follies, which can end in an avalanche accident or injury requiring a search and rescue mission. The Kirkland friends’ story “makes me cringe a little bit,” admitted Scott Schell, director of the Northwest Avalanche Center (NWAC), though he saw shades of his first backcountry outing, as a teenager during the winter of 1986-87, tramping up Panorama Point at Mount Rainier with downhill skis on his back, oblivious to avalanche hazard. “It was a total junk show,” he said. “We all began somewhere.”

This winter, Schell hopes the backcountry-curious will begin by checking out the center’s Basics for Backcountry Winter Recreation, where skiers can find NWAC’s slate of avalanche awareness classes (all online this season), then consider further steps, like hiring a guide to learn backcountry technique 101 and signing up for a “Level 1” avalanche course certified by the American Institute for Avalanche Research and Education (AIARE). And evo also has a new online portal, the Backcountry Adventure Center, with online tutorials by Whistler-based Altus Mountain Guides that will go live Dec. 14.

Like the equipment itself, a seat in an AIARE Level 1 course is also a hot commodity this season. Seattle-based guiding outfit and mountaineering school Mountain Madness typically sees its first sign-ups for winter avalanche courses in the fall. This year, customers were champing at the bit in the summer, even before dates were posted. While instructor-to-student ratios are smaller to accommodate public health guidelines and classroom sessions will be virtual, Mountain Madness has sold out most of December and January, with February and March filling fast — a silver lining in a year that evaporated its international guiding business.

“We are looking at our biggest season ever and we have been offering these courses since the 1980s,” said Jaime Pollitte, Mountain Madness’ North American program director. “Hopefully we can help make this popularity trend happen smoothly by educating responsible and savvy backcountry users. The first priority is to keep people safe. The second priority is to covet your secret stashes, because it is going to get crowded out there.”

New backcountry travelers, like Ballard resident Riley Flynn, 23, are partly driving this demand. Flynn grew up skiing at Mount Baker, which has a mature backcountry scene. He has long been eager to experience the snow beyond the rope line. “You get to a point where you explore every nook and cranny inbounds,” he said. But finding friends willing to invest in the expensive gear and commit to an avalanche course was an obstacle. Until Crystal Mountain announced it was closing down for the remainder of last season as Flynn and his roommate were heading home from a day on the hill.

“COVID added fuel to the fire,” he said. “In the past I couldn’t convince any friends [to try backcountry skiing]. Now I have at least three.”

Backcountry skiing appeals to more than just guys in their 20s, however. Shoreline physician Kristen Johnson, 45, dragged her family of four up the Skyline Lake Trail across from Stevens Pass on snowshoes with skis strapped to their packs when the resorts closed last season. As someone who loves both skiing and hiking, she found the experience of climbing uphill to then ski down to be a light bulb moment. “This is amazing,” she recalled.

This winter, Johnson, her husband and their 14-year-old son are taking an AIARE Level 1 course with an eye toward ski touring around her husband’s family’s vacation home on Priest Lake in Idaho. “[The pandemic] was a push to do something I might not otherwise have been pushed to do.”

Outfitting for backcountry skiing doesn’t come cheap. Evo salesperson Bates Tillman estimates all the necessary equipment comes out around $2,200 MSRP — and that’s before spending around $400 on an avalanche education course. Flynn shopped end-of-season deals and still spent $1,500. Used and heavier gear can net cost savings. Wyatt Schulke, 24, a diesel mechanic from Granite Falls, declined to renew his season pass at Stevens Pass this season over the risk of missing powder days due to the reservation system. He plowed that savings into a backcountry rig that cost $400. Now he’s looking to outfit his fiancée and enroll her in clinics with SheJumps, a nonprofit that connects women with outdoor opportunities, to improve her skiing.

After three outings already this season, Schulke has no regrets but did learn a hard truth. “I realized I’m out of shape,” he said. “Sitting around for a couple months did me no favors.”

Adequate fitness and ski ability for aspiring backcountry skiers are major bugaboos for Martin Volken, a Swiss mountain guide who settled in North Bend and wrote a seminal guidebook to backcountry skiing in the Cascades and co-authored a backcountry skiing technique book.

“It’s not just about avalanche danger,” he said. Without those fundamentals, he argued, “You’re not going to be able to competently move through a backcountry winter environment.”

All the more so in the Cascades, where thick forest guards most alpine zones and a maritime climate leads to wildly fluctuating snow conditions from day to day and even between elevation bands — like pristine powder up high and knee-twisting, heavy snow down low. Those conditions make for a high barrier to entry for those seeking to take up backcountry skiing in the Pacific Northwest. “There is not a high-quality beginner ski tour in Western Washington without avalanche danger,” said Volken.

Tillman puts it more bluntly with evo customers: “Can you ski everything on the mountain [at the resort] and can you ski it in the worst conditions? If you can’t comfortably get down anything on the mountain, any day of the week, no matter how the snow is, then you’re not really ready.”

As for Montecucco and Tagliano of Kirkland, they are taking a Level 1 avalanche course this month from Volken’s company, Pro Ski and Mountain Service.

“We are pretty determined not to do anything dangerous this season,” Montecucco said. “We plan to keep it low-angle and low-risk. It’s still fun without doing anything too scary.”